Historical Dramas

Much of World Communities’ work has been creating plays which come out of the culture and history of various communities throughout the country. These types of plays have gone by lots of titles, whether historic drama, outdoor drama, or community-based theater. The goal of these plays are to articulate the story of the place they are performed in a way that involves the community in the writing of the work. While often professional, equity productions, these shows also involve some of the community in the production of the work. They are usually annual events that run for an extended time each year, and act less like plays and more like tourist attractions. Unlike typical community theater or even regional theater, through a broader marketing campaign, these community-inspired Historical Dramas seek to draw 80-percent of their audience from beyond a 60-mile radius of the play, thereby contributing to the local economy through the influx of tourists while also creating a sense of cultural pride.

Creating big, epic dramas out of the history of the place where they are performed is an art form that has ebbed and flowed over the years. Traditionally, most efforts have followed the examples of Paul Green’s “The Lost Colony” on the coast of North Carolina, or Kermit Hunter’s “Unto These Hills” performed at the Indian Reservation in Cherokee, North Carolina. Increasingly, newer models of production have sprung up including the creation of plays in restored historic structures or other unique settings, and for shorter runs, or sometimes semi-annually. The challenge is to find the right play and the right production model for the circumstances. The fundamental rule of successful Historical Dramas is that substance precedes structure: the material for the play and the circumstances under which it is produced should determine the structure of the work and method of production, and not vice versa.

Through Partnership Playwriting, the creation of Historical Dramas is a wonderful exchange of information for perspective. The playwright arrives knowing little about the culture or events he is going to write about but is driven by a curiosity to read and to interview and to explore all aspects of the community who have entrusted their story to him. In exchange, he offers artistic perspective: the ability to see what is unique and important in that which has become familiar. The story realized has to be of broader significance so as to draw people from outside the area.

In the end, a successful historic drama evokes pride in the region and creates opportunities to work side by side often with professional actors and directors. It is particularly beneficial when it attracts people to rural locations, drawn to a story they would never have known in a place they might not have otherwise visited.

The Reach of Song

Southern Appalachia

An Appalachian drama, it is also the story of rural America before and after World War Two. So moving, it was named the State Historic Drama of Georgia.

Prayer of America

Monongah, West Virginia

What happens when everyone and everything you’ve known is gone except for the children who need you? The story of immigrant women after America’s deadliest mine disaster.

Jimmy and Billy

Plains, Georgia

As Jimmy Carter rose to be president, his brother Billy rose a beer above his head—again and again. Except it was a lot more complicated than that.

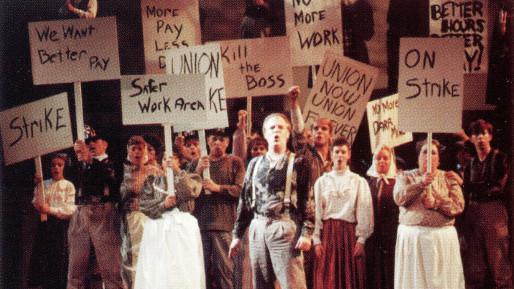

Streets of Gold

Western Pennsylvania Coal Fields

Industrialized America was fueled by the coal beneath the earth and the miners who came from all over the world to create a new day. Their story continues through generations.

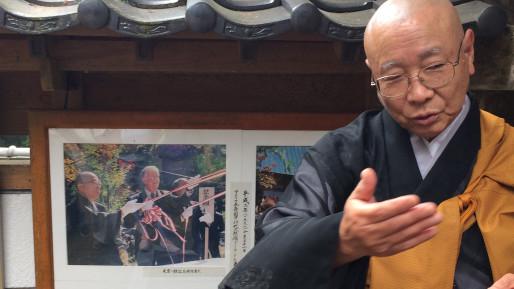

Birth of a Spirit

Japan

The play began in the home of a president and traveled to the town in Japan where it most resonated. Carter’s fight against racial prejudice reveals the birth of his spirit.

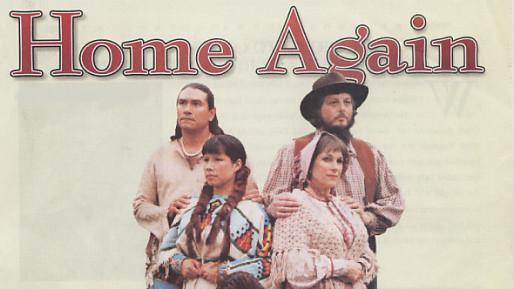

Home Again

Oregon City, Oregon

America’s great westward expansion created a juggernaut of cultural misunderstanding between pioneer and Native American cultures that this play tries to resolve.

Following Our Fannie

Americus, Georgia

What were once vaudevillians later became circus people. This play reunites the two in telling the story of a historic theater.

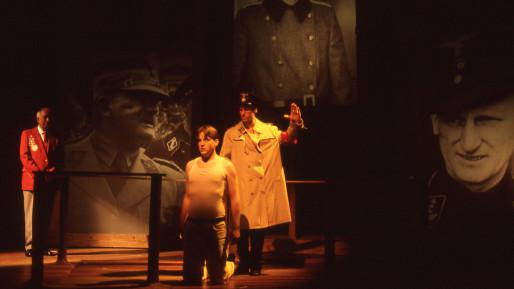

The American POW Drama

Andersonville Civil War Stockade

American Ex-Prisoners of War from many conflicts take their stories to the stage in this courageous and moving drama set within the context of wars’ very first prison.